Europe’s Roma communities speak out

The Roma, Europe’s largest ethnic minority, have suffered persecution for decades. In the Czech Republic, some are drawing parallels with the BLM protests against racism – and starting to speak up about their own experiences

By Anna Koslerova

This feature is accompanied by images from photographer Anna Veronika Krizova, who spent time travelling with Slovakian Roma families

Photo / Anna Veronika Krizova

“These are animals, not children,” Jira Turjanska heard a man at the neighbouring table say. She had just entered a buffet restaurant in Prague with a group of 12-year-old children, all of Roma descent. “He pushed one of the Romani boys to the floor,” recalls the 26-year-old, who works as an educational specialist with children from disadvantaged backgrounds. “The child ended up with concussion and a displaced vertebrae.”

Sadly, this type of incident, which took place earlier this summer, is far from unusual. Roma children face deep-rooted prejudices from a young age, in many parts of Europe. In the Czech Republic, where Jira lives, Amnesty International has reported they “have for decades suffered systemic discrimination.” As well as facing hostile attitudes and abuse in everyday life, children are often placed in schools designed for those with learning difficulties, or segregated in Roma-only schools and classrooms.

But the recent Black Lives Matter protests have been encouraging for some members of Europe’s largest ethnic minority. In the Czech Republic, press reports drew parallels between the issues, and many young people, both Roma and non-Roma, took to social media to discuss the similarities. Now, some in the community are trying to raise awareness of what they have suffered over the years, as well as reclaiming and celebrating their culture.

“I am sort of Romani, but since I grew up with white parents, I am not entirely sure what I am.”

“The protests resonated within the Roma community, but very few had the courage to speak up,” says Jira. “Nothing will change, but knowing that some Czechs connected the dots between this global movement against racism and the situation regarding the Roma population feels comforting.”

When I first met Jira, she was unsure if her story would be of any value for me. “I am sort of Romani, but since I grew up with white parents, I am not entirely sure what I am,” she explains. She remembers clearly the day she was handed over to foster parents aged four, shortly after her diagnosis of “light mental retardation”– an entry stamp for special needs schools.

“I was fortunate to have a blonde, blue-eyed mother who fought to keep me in a regular school,” says Jira. She is now completing her bachelor studies in pedagogy at Charles University in Prague, and is also working as an educational specialist with children from disadvantaged backgrounds, many of whom are Roma.

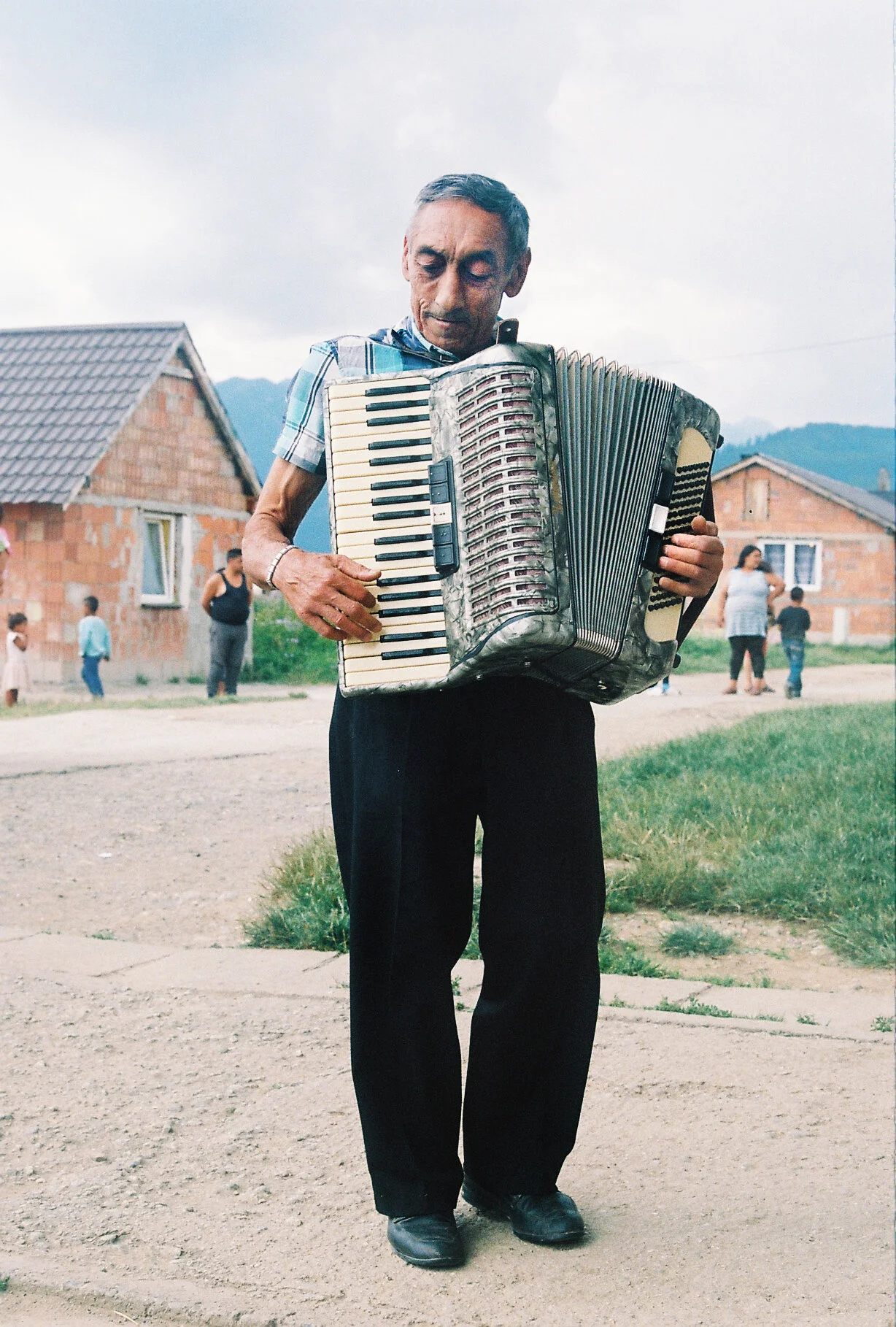

A Roma man plays the accordion.

Photo / Anna Veronika Krizova

The degrading treatment of Roma children in the Czech Republic has been criticised by the UN and by EU-based NGOs. In 2000, 18 children filed a complaint to the European Court of Human Rights against the widespread placement of Roma children in special needs schools and their disproportionate diagnosis with learning difficulties. In 2007, the court ruled that the Czech state had violated article 14 of the European convention, which prohibits discrimination, and article 2 which secures the right to education.

How much has changed since? There are still 13 schools in the country where Romani children make up over 90% of the students, and 70 that are more than 50% Roma.

In 2017, almost 1 in 8 Roma children of primary school age were following a reduced curriculum programme designed for those with learning difficulties, and in 2018 almost 30% of all children in special needs schools were of Roma descent.

Roma make up 2.2% of the overall population in the Czech Republic – around 240,000 people. Their history and culture are however not part of the Czech school curriculum. There is little awareness throughout society of the genocide perpetrated against Roma people by the Nazis, nor of the forced sterilisation of Roma women that took place during Communist rule in Czechoslovakia.

“Knowing that some Czechs connected the dots between this movement against racism and the situation regarding the Roma feels comforting.”

“The problem is circular: many Roma parents face a dilemma of whether to put their children in special schools because they fear bullying from the other children,” says Jira. “Often, many parents studied at a special school themselves and don’t know any better.”

Jira was often the target of racist remarks from her teachers and peers at her mixed school. “My humanities teacher would regularly ridicule me in front of the class, saying Roma had no place in higher education,” she said. She recalls how, whenever something went missing she was first to be blamed. “I didn’t know much about the Roma, other than that I didn’t want to be one,” she remembers. She also got used to asking friends whether their parents minded her darker skin and Roma roots before she visited their houses. “I learned to make myself small. It seemed normal to ask.”

When Jira was 18 she met her biological parents for the first time, and was inspired to start learning the Roma language. “To the Czechs I was Roma, and to the Roma I was Czech,” she remembers. “The only way forward is to teach people who the Roma are, and about their language and history of oppression.” Through her social work for the NGO People in Need, she hopes to one day teach others to appreciate the culture of a minority that counts 12 million people across Europe.

A young Slovakian Roma girl.

Photo / Anna Veronika Krizova

She’s certainly not the only one. “Change needs to start from primary school age,” says 32-year-old Michal Dord, founder of Vteřina Poté, a civil society organisation that lobbies for fair conditions within the social care system. I met with Michal in a garden outside the art school café in Prague. Despite us speaking Czech together, when a man approached to ask for a lighter, he addressed us in English after looking at Michal. The exact same thing occurred when I was sitting in a different café with Jira. She told me this happens all the time.

Michal tells me he was placed in state social care when he was just eight months old, after a social worker arrived on his mother’s doorstep armed with pepper spray and forced him away from her. His mother made several attempts to convince the courts she could take care of her son herself, largely in vain. When Michal was four, his mother was barred from visiting him in the institution he’d been placed in. “The institution staff said she was too interested in me and would attempt to bring me back home,” remembers Michal.

He says he didn’t know there was anything unusual about his childhood until he started primary school. “Children asked me about my dad, what he does and what he looks like, and I had to tell them I didn't have a dad,” he says.

“I didn’t know much about the Roma, other than that I didn’t want to be one.”

He first spoke to his father aged nine, when he called the institution.“I remember a man on the other end, he was crying and apologising,” he says. “I didn’t think much of it until he came to visit. I remember calling him my uncle and him telling me he was my dad.”

“Nowadays, he calls me all the time, to check on me, to ask how I’m doing. Sometimes even too much,” laughs Michal.

It took him 26 years to understand the full story. “I didn’t believe it until I saw it on paper,” he explains. Official court documents say that he was removed for socio-economic reasons. This practice has been outlawed since 2011 and yet, according to Michal, around 10% of all children in Czech institutions today are of Roma origin.

A Slovakian Roma woman and child.

Photo / Anna Veronika Krizova

Learning about his own past has motivated Michal to try and improve the lives of others. As well as his own organisation, he also works for the ministry of social care and is a formal member of the governmental body of children's rights. “I am convinced there are other stories similar to mine,” he says.

On top of education, finding safe and suitable housing is another challenge for many Roma.

I meet Iveta Kokyova outside a metro station on the outskirts of Prague. After a firm handshake and a cheerful smile, she offers me a cigarette. “I’ll take you to my sister and we’ll tell you our story,” she says.

Iveta recalls how it recently took her family an entire year to find a home for her 26-year old daughter and her three children. Landlords and real estate agents would openly tell them that Roma tenants were a “no-go.”

“Suddenly, you have three generations with unfavourable views of us, despite not knowing anyone of Roma origin.”

“I started thinking I was paranoid, until one viewing where the landlord angrily shouted at the estate agent for bringing over ‘dirty gypsies’,” the 48-year-old says. Iveta warned them about how that violated fundamental rights, “but no one cared.”

When they finally found a place in 2019, the landlord requested three guarantors and several months of rent upfront. But even that wasn’t the end of it. “Once my daughter and her family moved in, the neighbours started filing complaints about gypsies in the house.”

“No one learns about the Roma in school, and people fear what they don’t know,” says Iveta. “Stereotypes are handed down from grandparents to parents and to children. Suddenly, you have three generations with unfavourable views of us, despite not knowing anyone of Roma origin.”

Two Slovakian Roma boys and their pet dogs.

Photo / Anna Veronika Krizova

Iveta and her sister Dana grew up on the fringes of society. “The city council placed our family in a small house opposite the dumpyard,” says Dana. Iveta adds: “We got used to the awful smell that greeted us on the way to school every day – we literally lived where our classmates dumped their rubbish. It felt like we were rubbish.”

Nowadays, Iveta is a published novelist writing in Czech and Roma, a mother of three and grandmother of six. After 17 years as a stay-at-home mum, she decided to go to university at the age of 36 and pursue Roma studies. Dana is a social worker for the local council.

“My husband was scared I’d start studying the Roma from an outsider's perspective and would become a ‘Gadje’ [the Roma word for non-Romani],” explains Iveta. “But the opposite has happened. I feel like I’ve had the chance to finally learn about, and be proud, of my own heritage.”

“I sincerely hope my grandchildren will be proud Romas, that they will feel no shame in speaking the language and dancing to Roma music.”

Iveta’s dream is to teach the Roma language, which has many dialects depending on your country, region and family. “Both my parents spoke different dialects so I know different varieties,” she says. “But writing is a struggle because no one uses it and no one teaches it.”

Iveta says she has done her best to pass on the language to her children and is currently teaching her grandchildren. “It’s the best gift I can offer them,” she says.

After my interview with Iveta and Dana, the sisters insisted I join them for a party where Trio Romano, a Roma band, was playing. We ate grilled sausages and Iveta and Dana sang along in a striking variety of languages: Roma, Hebrew, Spanish and Czech.

“I sincerely hope my grandchildren will be proud Romas, that they will feel no shame in speaking the language and dancing to Roma music,” says Iveta. “Most of all, I hope they will never experience what it feels like to be on the outskirts, to be those living opposite the dumpyard.”