How I rediscovered

my family story during Krakow’s lockdown

By Christian Davies

Janina and Stefan, Podhajce, mid-1930s.

I owe my existence to a sausage-dog.

In 1940, my maternal grandparents were living in fear for their lives in the Soviet-occupied eastern Polish city of Lwów – now the western Ukrainian city of Lviv, once Lemberg, the capital of Austrian Galicia.

The Soviets had crossed into eastern Poland on 17 September 1939, as part of the joint Nazi-Soviet operation to divide, conquer, and ultimately eradicate Poland as an entity capable of resistance. In both zones of occupation, military operations were accompanied by state-directed campaigns of terror and mass killing against the many categories of citizen deemed by the occupiers as potential enemy elements.

In the Soviet zone, these campaigns were carried out by the NKVD, the Soviet state secret police. Even before the outbreak of war, in 1937-8, it had carried out an operation of mass murder of over a hundred thousand Poles in the western Soviet Union. Within months of their entry into eastern Poland, tens of thousands of Polish citizens had been killed in mass shootings, with hundreds of thousands more deported to the Gulag.

My grandparents had reasons to fear the NKVD that went beyond their Polish nationality and bourgeois backgrounds.

My grandfather, Stefan, a land surveyor, had studied forestry as a young man, making him a top priority target for the wily Soviets, who grasped that people with knowledge of local forests would be key to organising partisan resistance.

Helena Kubisztal (née Wospiel), c. 1904. Helena died at the age of 21 giving birth to Janina in 1907.

My grandmother, Janina, was arguably the principal target. Her mother Helena had died in childbirth and her father, Adam Kubisztal, later a high-ranking military officer, had left her to be raised by her grandparents. An officer in the Austrian Army before the First World War, Adam had joined the newly-formed Polish army after the creation of an independent Poland in 1918, running a prison camp for enemy combatants during the 1920 Polish-Bolshevik war. The fact she had had no contact with her father for years (he had long since left for western Poland) and had no idea of his whereabouts only exposed her to an even greater risk of interrogation and torture.

Stefan and Janina had already had a very near miss in the small town in which they had been living when the war broke out, when the NKVD had come knocking for them at the wrong address. Tipped off by their neighbours, they felt their best chance was to lay low in Lwów.

There, they lived in an apartment to which a senior Red Army officer, a Russian, and his family had been billeted. Then a childless couple, Stefan and Janina bonded with the officer and his wife and little daughter.

One day, the NKVD came knocking again. The Russian officer, no friend of the secret police, told Stefan and Janina to hide in a back room together with their little sausage-dog, Miluś (‘Cutie’). Answering the door, he told the NKVD officers that his Polish ‘hosts’ had long since fled the city. Whether by sheer luck or out of some canine intuition, Miluś, who would always go berserk at the first sign of visitors, kept quiet for the first and only time in his life.

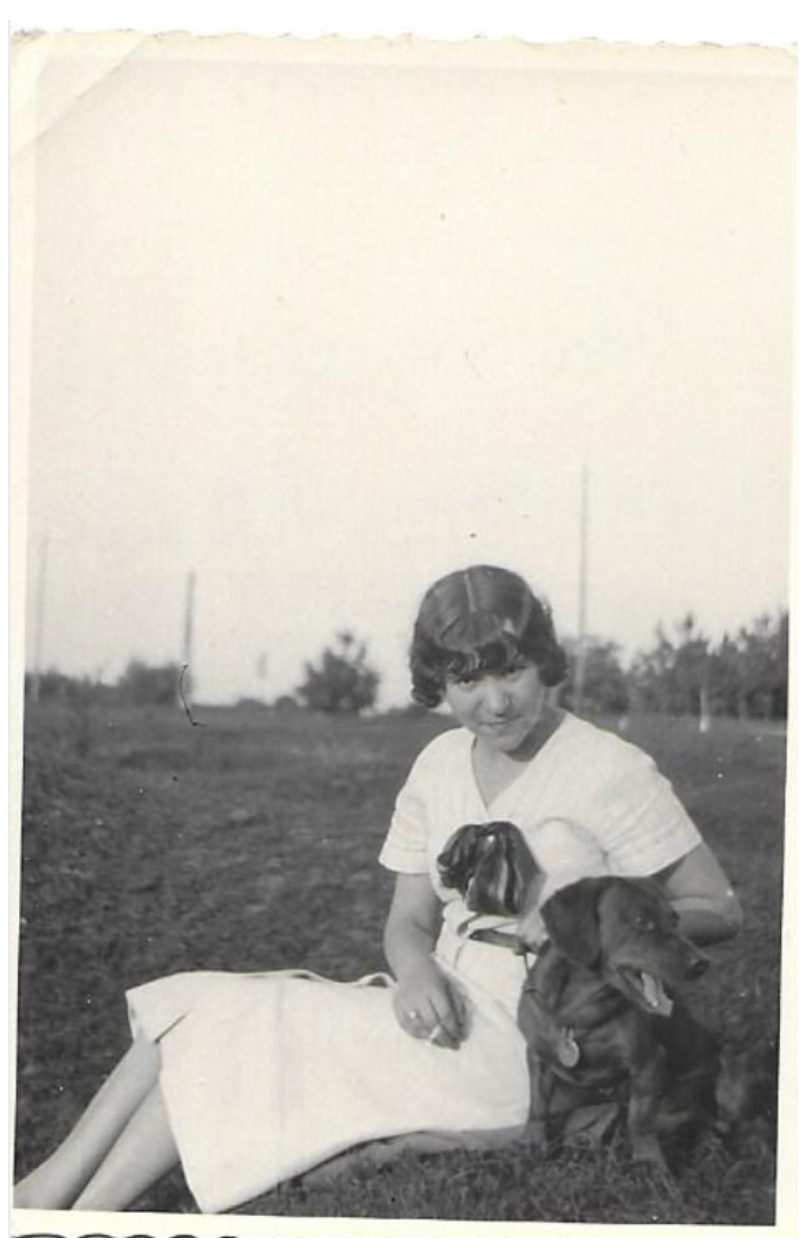

Janina and Miluś, Brody, 1938. Miluś' silence when the NKVD came knocking in 1940 saved their lives.

Of course, it is the Russian officer, not the dog, who saved the lives of my grandparents. But the way the story was told to me when I was growing up, little Miluś takes the credit.

*

Like many Polish families, especially those from beyond the Polish heartland that straddles the Vistula, we are not really all that Polish at all – at least in our origins. We are not products of the soil, but of contingency – of events, of wars, of border changes, of decisions made by imperial bureaucracies, of migrations borne of persecution and economic opportunity. As Galicians - and now as Europeans - our family stories are characterised as much by our experiences of separation from home and from one another as they are by a shared connection to a particular place.

Janina and Stefan were both born subjects of the Habsburg Empire, in the Austrian partition of the old Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (1569-1795), a multinational dual state with ever-changing borders that included much of modern-day Poland, Ukraine, Belarus, and Lithuania. When the Commonwealth was carved up between Russia, Prussia, and Austria towards the end of the 18th century, the Habsburgs named their new province - made up of what now constitutes much of southern and south-eastern Poland and western Ukraine - the ‘Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria’, after the long-forgotten Kingdom of Galicia and Volhynia that had been ruled in the 13th century by the Ruthenian Daniel of Galicia (in Ukrainian: Danylo of Halych).

Janina Kubisztal in her teens, Lwów, 1920s.

The Austrians had never before ruled this territory, which was dominated by large populations of Polish and Ukrainian Slavs. Faced with this linguistic and administrative challenge, they turned to the empire’s Czech population as a source of loyal subjects better-suited for administering the new province. As Slavs who had lived in the Germanic Holy Roman and Habsburg Empires for hundreds of years, the Czechs straddled the Germanic and Slavic worlds, making them ideal candidates for the new Galician bureaucracy.

As a result, there was a significant migration of Czechs to Galicia, and specifically to Lemberg, the provincial capital, over the course of the 19th century – and it was from this Czech-Galician administrator class that Janina was largely descended. Her mother Helena’s maiden name was ‘Wospiel’ (in Czech: Vospěl); her grandmother Alojza’s maiden name was ‘Fiala’; the maiden name of her great-grandmother, also called Alojza, was ‘Mokko’. None of these names are remotely Polish.

Janina’s father, Adam Kubisztal, also had a distinctly un-Polish surname. ‘Kubisztal’ is almost certainly a Polonised version of the Swedish ‘Jacobsdal’, suggesting the Kubisztals were descended from Swedes who invaded Poland in the 17th century. ‘Jacobsdal’ was the name of the palace of the Swedish statesman and field commander Count Jacob de la Gardie, who led several Swedish military incursions into the Commonwealth, with records suggesting that Adam’s ancestors on his father’s side came from the area around Tarnów in southern Poland, where there are several Swedish fortifications.

Adam Kubisztal, c. 1898. Adam was a military lawyer who served in the Austrian and Polish armies, rising to the rank of colonel. He moved away after Helena's death, starting a new family elsewhere.

Janina’s husband, my grandfather Stefan, had a more straightforwardly Polish name – ‘Korzeniewicz’, my mother’s maiden name – but with a no less complex family history. Like many other members of the Polish gentry, the Korzeniewicz clan had migrated eastwards, most likely in the 16th century, from the Polish heartland after the 1569 union between the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. There, they settled in the rural expanses of the Grand Duchy, a plantation of Polish Catholics into the majority Orthodox Ruthenian (Ukrainian and Belarusian)-populated lands that was broadly analogous to the Protestant plantations of Ireland that were going on at the same time at the other end of the continent.

Stefan Korzeniewicz in his 20s, Lwów, 1920s.

In the Grand Duchy, the Korzeniewiczs were part of a privileged class called the ‘walled-off nobles’ – clans who were noble in status but economically relatively deprived, forcing them to work the land but keeping themselves separated from the surrounding peasantry by shutting themselves off in walled communities. After the Commonwealth’s collapse, however, they found themselves relatively lowly and mistrusted subjects of the Russian Empire, in an area that is now part of modern Belarus.

In the 1870s, Stefan’s father, Leon Korzeniewicz, left his home near Pinsk and ran away to Galicia. His motivations were two-fold: in addition to escaping forced conscription into the Tsarist armies, he had also suffered religious persecution as a Greek Catholic (sometimes known as a ‘Uniate’, a member of an Eastern Orthodox denomination centred on Ukraine and Belarus that in response to Muscovite pressure had formed a union with the Roman Catholic church). Settling in the Austrian partition, where Greek Catholics were allowed to practice their faith, Leon made a life for himself first as a teacher and then as a postmaster, building a house in the village of Zbarazh some 150 km east of Lemberg.

Stefan Korzeniewicz and his mother, Stefania, in front of the family home in Zbarazh, mid-1930s. Stefan's father Leon built the house in Zbarazh after running away from the Russian Empire to Galicia.

And so, in the early 20th century, Janina and Stefan would both be born into Galician families, marrying in 1929 in what had become the eastern Polish city of Lwów. They lived in a succession of smaller Galician towns throughout the 1930s, and were living in the town of Brody – now best known as the birthplace of the novelist Joseph Roth – when the Soviets invaded.

Janina and Stefan survived the war in Lwów, which had endured three waves of occupation – by the Soviets in 1939, by the Germans in 1941, and by the Soviets again in 1944. The mild-mannered Stefan had worked as a stretcher-bearer at a hospital – a humanitarian role that brought him into contact with unimaginable horror. At the war’s end, they found themselves part of a westward wave of Polish refugees from eastern Galicia and the neighbouring province of Volhynia, fleeing both Soviet-mandated population exchanges and ethnic cleansing at the hands of Ukrainian nationalists.

Ravaged by Soviet and German occupation, Galicia and all it represented had been destroyed. Populated by Poles, Ukrainians, and Jews, the Jewish population had been exterminated in the Holocaust, often with the assistance of non-Jewish local people. In scenes redolent of the partition of India a few years later, the destruction of the Galician Jews was followed by extreme intercommunal violence between the remaining Poles and Ukrainians, many of whom had lived together and intermarried and shared a common hybrid culture for hundreds of years. Stalin finished the job, forcibly exchanging minority populations across the new Polish-Ukrainian border on the River Bug in a successful attempt to create two ethnically homogenous buffer zones where an ethnically and confessionally diverse province had once been.

With almost no connections in Poland proper, Janina and Stefan made their way to Tarnów, a picturesque city located between Lwów and Kraków, and home to a distant branch of the Kubisztal clan. They ended up staying in the area, moving to Dąbrowa Tarnowska, a nearby ghost town where the population before the war had been 70% Jewish. It was there, in the aftermath of the war, as the Communists were asserting their control over Poland, that my mother was born.

*

Janina never fully reconciled herself to the loss of her Galician homeland. She would pine for Lwów, making no effort to hide the fact that she considered her new life in Dąbrowa Tarnowska a disappointment. She drummed into my mother the notion that “this is not where we are really from”, and the message cut through. Perhaps this is why my mother has never taken me there – despite the fact that nearby Kraków is our second home, it was only last year, at the age of 33, that I first made the one-and-a-half-hour journey to see my mother’s hometown.

As a literature student at the Jagiellonian University in Kraków in the late 1960s, my mother was part of the student generation of ‘68, famous in Poland for mobilising in opposition to the communist regime. The Polish Communist party, which was already engaged in a factional struggle between nationalists and so-called ‘cosmopolitans’, many of whom had Jewish backgrounds, responded to the student unrest by whipping up popular anti-Semitic sentiment, blaming disloyal ‘Zionists’ for destabilising the country. The campaign led to tens of thousands of Polish Jews - much of the remainder of a community that had been decimated by the Holocaust a quarter of a century before – being forced to leave the country.

(Decades later, I would report on the fiftieth anniversary of the so-called anti-Zionist campaign for the Guardian, as Polish Jews held a ceremony at the Warszawa Gdańska railway station beneath a plaque bearing a tribute from the Polish-Jewish writer Henryk Grynberg: “For those who emigrated from Poland after March 1968 with a one-way ticket. They left behind more than they had possessed.”)

My mother remained in Poland throughout the 1970s, completing a doctorate decoding the obscure, mystical Romantic verse of the 19th century poet Juliusz Słowacki and teaching literature at the Jagiellonian University. By the turn of the decade, however, she had had enough of the Polish People’s Republic, and when she was offered a job in France teaching Polish at the university of Clermont Ferrand, she applied to the government – as one had to in those days - for permission to go.

My mother arrived in France in November 1981, a matter of weeks before the imposition of Martial Law in Poland by General Jaruzelski’s regime. She spent Christmas alone in a wintry Paris, not knowing anyone in the city, cut off from her home country, not knowing what had happened to her family or friends and unable to contact them because the phone lines had been cut and postal services suspended. It was a cruel echo of the experience of her own mother, by now long widowed after Stefan’s death in 1974, still pining for her own, long-gone Galicia.

Maria Korzeniewicz, Paris, 1983. “I was free - from the Communists, and from my family.”

Having settled into life in France, my mother met my father, a British historian, who was visiting Clermont Ferrand to give a lecture. By the early 1980s, he had already had a relationship with Poland that went back two decades. He had been due to travel to the Soviet Union as part of a student group in 1962, but the trip had been hastily redirected to Poland after the Soviet authorities had refused to grant visas to the students, and the visit had so fascinated him that he would devote his career to the country.

This time, the historical echo was a little sweeter: the same border between communist Poland and the Soviet Union that had cut Janina and Stefan off from their homeland would – indirectly – be responsible for their daughter eventually meeting her future husband.

But if a border within the Soviet bloc helped bring my parents together, the borders between Soviet bloc countries and western Europe threatened to keep them apart. It was not possible for my mother, a Polish citizen, to move to the UK on a permanent basis, and on several occasions the strains of maintaining a long-distance relationship in the analogue age – even between Britain and France – almost proved too much for them to bear.

*

My parents finally married in London in 1984, and I was born in 1986; part of the generation of the so-called ‘89ers’, young Europeans who grew up after the fall of the Berlin Wall and for whom the borders that had shaped the lives – and the minds - of our forebears were no longer supposed to matter. As I grew up, it felt as though the barriers, separations, and indignities that had dogged my parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents were melting away.

Maria and Norman Davies, Kraków, 1984 - a few months before their wedding.

Borders are not just some administrative inconvenience; they are intensely personal, dividing families, testing relationships, shaping peoples’ lives in directions they may not wish them to go. Of course they are necessary in certain contexts, but until you find yourself on the wrong side of one, you cannot understand the effect they can have on a person.

Whereas as a very small child I had briefly been a citizen of the nasty, petty, authoritarian and eastward-oriented Polish People’s Republic, I would grow up a citizen of the Polish Third Republic, a liberal democratic constitutional order within a truly independent Poland that granted Poles rights and freedoms that so many had dreamed of for generations. Indeed, the creation of the Third Republic was in some ways the first step towards fulfilling a promise made over a thousand years ago, when in 966 the Polish king Mieszko I adopted Roman Christianity, a declaration that the destiny of his people would lie in the West.

In 2004, that thousand-year-old promise was fulfilled when the new republic, along with nine other countries, acceded to the European Union. It is difficult for many western Europeans to understand the emotional dimension of this event for citizens of these ‘new members’. To wait at the border with Germany, as Poles had to do previously, was not painful just because it was boring or inconvenient. It served as confirmation that you were not considered equal, that you were not considered trustworthy, that you are not there to be welcomed, but to be verified.

For just over a decade, it felt as though all of the strands of my identity and the experiences of previous generations of my family were being woven together. I was proud of the role that Britain had played in supporting the Solidarity movement, its role in pushing for the EU’s eastward expansion, and its policy of welcoming the citizens of the new member states without restrictions. I was even more proud of Poland’s achievements since 1989 – not just economically and politically, but in terms of confronting its past and engaging in reconciliation efforts with other nations. Through the UK and Poland’s common membership of the EU, it felt as though my two countries were finally part of the same moral cause.

That has only made the last five years all the more painful.

Since 2015, a narrow majority of Poles have continuously voted for a despicable authoritarian party that has sought to destroy the Third Republic, its democratic institutions and its achievements, trashing the nation’s once rehabilitated reputation and burning bridges with the outside world that had been painstakingly constructed over decades.

Then in 2016, a narrow majority of Britons voted to withdraw from the EU, a vote that was, in part, an explicit rejection of migrants from Poland – people like my mother. I had once assumed that if I were to fall in love with a Polish woman, as my father had done, then we would not face the administrative indignities and barriers to building a new life in Britain that my parents had. But that has turned to be a false hope; the UK may have regained some formal sovereignty as a state, but only at the cost of the personal sovereignty of its citizens. Whilst I fully understand that these barriers have long existed – and will continue to exist – for people whose heritage lies outside the EU, there is a particular pain in being granted such a precious sense of freedom and dignity, only for it to be taken away again just over a decade later.

I witnessed much of this process of unravelling in both the UK and Poland at first hand.

Between 2012 and 2015, I worked as a parliamentary researcher in the House of Commons for a senior Conservative MP, and watched from the inside as David Cameron’s Tory party drifted towards the declaration of an In/Out referendum. Then, as a foreign correspondent based in Poland since 2016, I witnessed up close just what an authoritarian government can do to a country.

It is not just the effect that it has on certain institutions, such as the media or the judiciary - it is the moral and spiritual damage it does to society as a whole. In recent years, I have interviewed judges and academic services being hounded by the security services and government-funded trolls, Polish Jews being told to leave the country, members of the LGBT community told they should be sent to the gas chambers, and rape victims who attempted suicide because their friends told them they deserved it. Over time, the sheer cruelty and injustice of it all – compounded by frustration that the outside world doesn’t seem to really understand or truly care about what is happening - puts a tiny, icy shard of hatred in your heart that wasn’t there before.

*

It took me some time to realise that the reversal of the progress made over the course of my lifetime, the steady unravelling of a world that I had felt the experiences of my ancestors was somehow building towards, was contributing at some level to a kind of personal malaise - and it was in the midst of this malaise that the coronavirus struck.

My experience of lockdown has not been arduous. Whilst punctuated with anxiety about my elderly parents back in the UK, we have – so far – survived unscathed. But as I sat here alone in Kraków, perhaps because I have had so much time to reflect on my own life and the emotions associated with the political and personal turmoil swirling around me, these family stories came rushing back to me.

Between March and May, I went eleven weeks without meeting another person, isolation compounded by the fact that my then-girlfriend and I had broken up a matter of days before the lockdown was imposed. I had packed my bags and left the flat we had shared in Warsaw, moving into my mother’s flat in Kraków.

The flat, though in a relatively new building, is itself a reminder of the past. In order to prevent the communist authorities from confiscating her previous apartment in Kraków after she had left for the West, she had signed ownership over to some friends, a trio of sisters, who would take care of it and have use of it until her return. But years later, after communism fell and she returned to ask for her flat back, the sisters simply refused to return it.

Christian and Maria Davies in Lviv, November 2017.

My mother was helpless, having no legal grounds for getting the property back, since she had willingly signed it over. The sisters own it to this day. But in the early 2000s, my father saw that a new block of flats was being built further along the same street as the flat my mother had lost, buying it in recognition of the fact that she had never gone back to reclaim her property earlier because she had fallen in love with him and moved to the UK.

This new flat, therefore, carries with it the reminder of what was lost – not just by my mother, but also by her parents, who amidst the turmoil of the end of the war had been forced to abandon both the Korzeniewicz family home in Zbarazh and the plot of land in Brody which they had bought just before the war in anticipation of building a house there. Both now lie in Ukraine.

Property restitution remains a fraught and sensitive subject in this part of the world. Those who have never lost family property in this way often think that property restitution is about money, but it is about so much more – it is about regaining some part of one’s self, justice for your family, a physical legacy of relatives and loved ones you may have never met or may never see again. We never got our properties back, nor did we receive any compensation, but we were fortunate enough to be able replace them. Others are not so lucky.

To cope with the solitude, I would take endless long walks around the city, struck by all the little ironies of my situation. My ancestors had been constantly moving: my Czech ancestors had entered Austrian Galicia as administrators; my Swedish ancestors had entered the Kingdom of Poland as soldiers; the Korzeniewicz clan had entered the Grand Duchy of Lithuania as settlers. Leon Korzeniewicz had left the Russian Empire and moved to Galicia; Stefan and Janina Korzeniewicz had left Galicia and moved to Dąbrowa; my mother had left Dąbrowa and moved to Kraków, then France, then the UK. I was born in the United States and raised in the UK, but had ended up in Kraków again. In Dąbrowa after the war, Janina had been cut off from Lwów; in Paris, my mother had been cut off from Janina. My mother was then cut off from my father; now my parents are together, but they have been cut off from me.

As I walk around Kraków, I pass the street where Stefan died and the cemetery where he is buried. I pass the university department where my mother studied and taught, and the apartment she had owned before she departed. I pass the student residence where my father stayed when he first arrived in Poland in the 1960s. And I pass the bars, restaurants, parks, squares, and streets where I have enjoyed some of the happiest moments of my own life. As I walk, I am accompanied by two recurring thoughts: I am no longer a foreigner here, and I am not alone.

*

Perhaps it is the Galician in me, but I believe in unions. Some may consider professions of faith in notions of co-operation, solidarity, reconciliation and atonement between and within nations as naïve or idealistic. They are not – they are rooted in experience, in bitter experience, in wisdom borne of trauma. The alternatives are always worse.

Our family experiences are by no means exceptional – indeed, given the fact that my immediate ancestors were located at the heart of the so-called ‘bloodlands’ of Central and Eastern Europe, they were remarkably fortunate to emerge with their lives intact (my father’s family, for example, suffered significantly more immediate family tragedy in the First World War than my mother’s family in the Second). My grandparents may have been refugees, and may have suffered for it, but one cannot lose sight of the fact that they were able to build a new life in a town where the majority of the population had only recently been exterminated simply because they were Jewish.

But violent displacement and numerous near-death experiences, not to mention what they would have witnessed in wartime Lwów, still take their toll. Janina and Stefan had dealt with this burden in very different ways – whilst the demonstrative Janina had raged and mourned and lamented, the unprepossessing Stefan, who had been profoundly affected by his experiences as a stretcher-bearer, had like so many of his generation preferred simply not to mention it. Having seen what bitterness had done to her mother, my mother had adopted Stefan’s approach: ‘I’ve been silent for years because I’ve refused to be swamped and destroyed by memory, by ghosts from the past’, she wrote to me recently.

The anxiety never quite goes away, but it can be soothed. In 2016, a few weeks after the Brexit referendum, I travelled to Ukraine intent on finding the house in Zbarazh that had once belonged to Leon Korzeniewicz, my great-grandfather who had run away from Pinsk to Galicia.

No-one from the family had ever been back since the war. In the 1970s, my mother’s uncle had, from memory, drawn her a map in pencil of the house’s location in relation to local roads and a nearby river – the only document we had to guide us. Thankfully, it had proved remarkably accurate, so much so that it aligned perfectly with a Google satellite image of the village.

Armed with satellite coordinates and having rented a car in Lwów and weathered western Ukraine’s truly appalling roads, I arrived in Zbarazh and soon found the house’s location. Poignantly, it was just down the road from a tiny Roman Catholic chapel, which still stood but without a roof, its altar and interior overgrown with weeds, a reminder of the Poles that had long since gone.

The house that stood on the plot was not the house that Leon Korzeniewicz built, the house outside which a happy Stefan appears in several photographs. The owners of the new house were not in, but a neighbour told me that the old house had only been knocked down a few years before. In front of the house, however, was a cherry orchard – the cherry orchard Leon Korzeniewicz had himself planted, clearly marked on my mother’s uncle’s map.

I have little interest in securing financial compensation for that property or the land that surrounds it – much of which, on a hot summer’s day, was strikingly beautiful. I feel no ill-will towards the Ukrainians who live in Zbarazh now. I never met Leon Korzeniewicz; I never even met Stefan Korzeniewicz, Leon’s son and my mother’s father. I have only visited his grave. Indeed, I had not expected to feel particularly emotional in that little village at all.

Leon Korzeniewicz in his cherry orchard, Zbarazh, 1930s.

But standing and looking at Leon’s cherry trees, it occurred to me that throughout my childhood and until I reached the age of about thirty, my mother had remained almost completely silent about her family, long convinced that no good could come from me carrying these stories with me through my own life. And yet here in front of me, in these cherries, just as I was trying to come to terms with the imminent loss of a world I grew up believing in, was a tangible connection to a world that had been hidden from me, a world that had already been lost long before. I reached over the fence and took a single cherry, claiming it as my inheritance. I can still taste it now.